DARIAH-CH Study Day - Back and Forth from Boundary Objects to IIIF Resources (Poster Script)

DARIAH-CH Study Day - Poster Script

- Title of the poster: Back and Forth from Boundary Objects to IIIF Resources. The Recipes of a Community-driven Initiative Specifying Standards

- IIIF Manifest of the poster displayed on Mirador

(Submitted) Abstract

The exchange of digital objects and their associated metadata is simplified when these meet established standards, but the capture of all the (meta)information is still very much in tension, at the limits of resources, knowledge and indeed the underlying capabilities of given standards. These limitations can be translated into what Susan Leigh Star defines as residual categories and consequently the generation of boundary objects. The question of these non-standardised residuals within the cultural heritage and digital humanities fields is an iterative identification issue that institutions and individuals have sought to mitigate.

Take for instance resources conforming to the application programming interfaces (APIs) of the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF). These are JSON-LD serialised objects duly specified and vetted by a community trying to break institutional silos. Of particular interest are resources compliant with the IIIF Presentation API which underpins what a Manifest is, i.e. a description of the structure and properties of the compound object which can be interpreted by a client and displayed to end-users, typically disseminated openly on the Web.

While on the surface or theoretically these IIIF Manifests, or compound objects, could be quite the antithesis of boundary objects, it remains to be seen to what extent IIIF-compatible resources revolve around residual categories and also from what point onward these Manifests have been at some point or revert to boundary objects, whether they are not well-structured or simply because the architecture and constituent software serving and interpreting them do not operate correctly.

Poster (verbose version)

Introduction

The exchange of digital objects and their associated metadata is simplified when these meet established standards, but the capture of all the (meta)information is still very much in tension, at the limits of resources, knowledge and indeed the underlying capabilities of given standards.

These limitations can be translated into what Susan Leigh Star defines as residual categories and consequently the generation of boundary objects 1. The question of these non-standardised residuals within the cultural heritage (CH) and digital humanities fields is an iterative identification issue that institutions and individuals have sought to mitigate. A good example still to be investigated are the resources conforming to the application programming interfaces (APIs) of the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF) 2, which have been growing in popularity in the CH field for the past decade for disseminating (image-based) digital objects at scale.

Boundary objects and residual categories

Star 3, in one of her last articles, revisits the often misused concept of boundary object and the temporality aspect illustrated in Figure 1, demonstrating to some extent the life cycle of a standardisation effort to restructure the residual categories that generated said boundary objects.

|

|---|

| Figure 1. Relationships between standards and residual categories. Adapted from 3 |

IIIF Resources

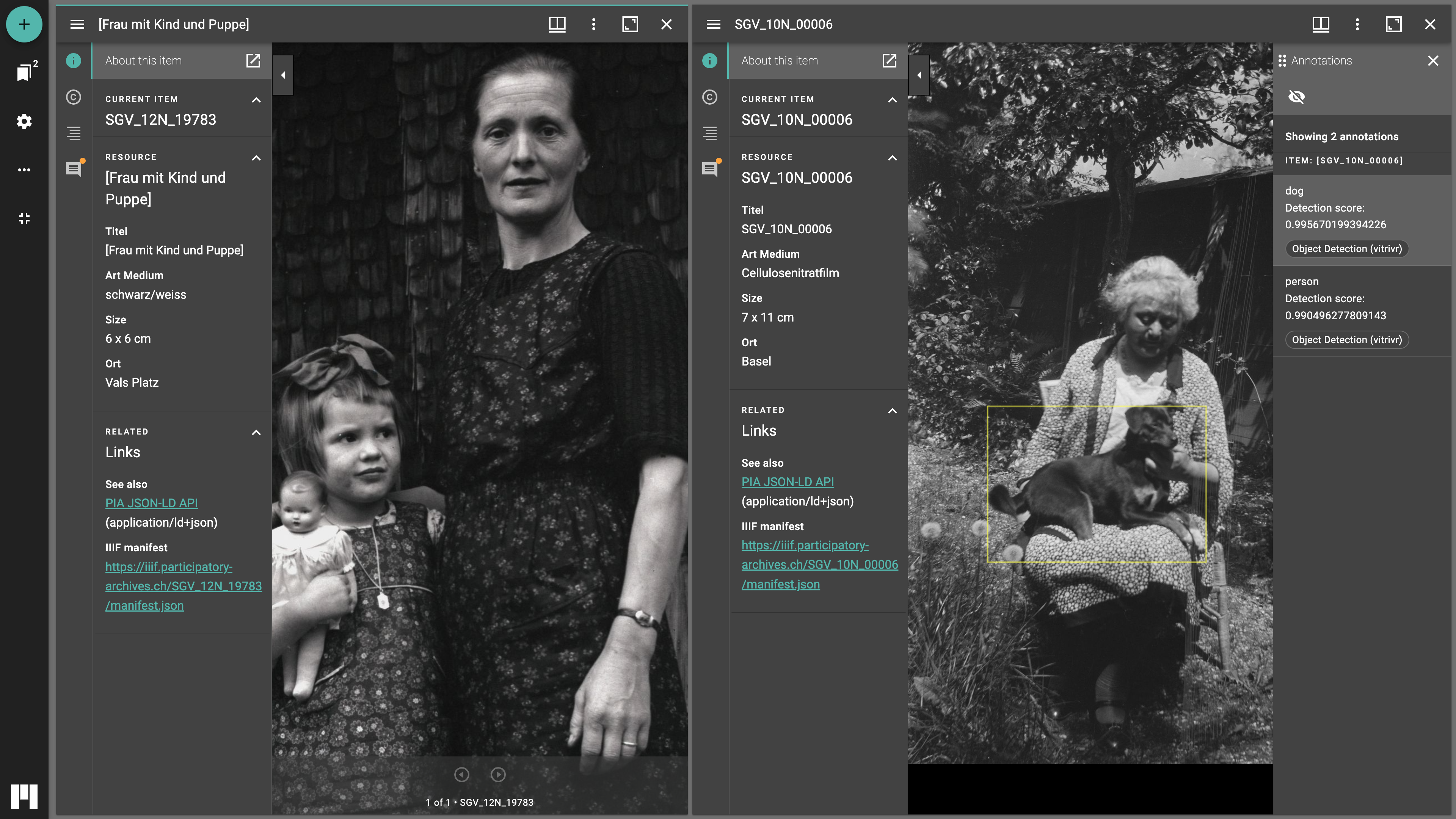

IIIF resources are JSON-LD serialised objects duly specified and vetted by a community trying to break institutional silos. Of particular interest are resources compliant with the IIIF Presentation API which underpins what a Manifest is, i.e. a description of the structure and properties of the compound object which can be interpreted by a client and displayed to end-users. IIIF Manifests are typically displayed through compatible viewers.

While on the surface or theoretically these IIIF Manifests could be quite the antithesis of boundary objects, it remains to be seen to what extent IIIF-compatible resources revolve around residual categories and also from what point onward these Manifests have been at some point or revert to boundary objects, whether they are not well-structured or simply because the architecture and constituent software serving and interpreting them do not operate correctly.

|

|---|

| Figure 2. IIIF Manifests generated as part of the PIA research project and displayed in Mirador |

The angular momentum of web objects

|

|---|

| Figure 3. Analogy to the angular momentum 4 and IIIF resources as spinning tops |

The interpretation of IIIF resources and their related features provides the initial entry point for most end users and are genuine mediators and not mere intermediaries, to echo the words of Latour 5. For determining what are IIIF-compliant resources, one indicator seems relevant to me: the support of patterns correctly interpreted by existing viewers, i.e. the cookbook recipes compiled by IIIF Community members.

Metaphorically, my idea is to make an analogy between web content, here IIIF resources, to spinning tops when they are at their augular momentum, which would mean that their rotational inertia (Ι) equals their compliance timeframe (L) as long as the angular velocity (ω) works as expected (1 ≡ yes). Each viewer would be a surface on which force is applied (cf. Figure 3).

As of September 2022, the Viewer Matrix lists currently 42 unique recipes - divided by functionalities or types - and their support (yes, no, partial) by Mirador, the Universal Viewer (UV) and Annona (cf. Figure 4).

|

|---|

| Figure 4. Viewer support of the IIIF Cookbook recipes (as of September 2022) |

Results

|

|---|

| Figure 5. Summary of IIIF Presentation API 3.0 viewer support as spinning tops (Mirador, UV, Annona) |

Conclusion

- A shift from rigid standards to software support is needed to perform analysis around boundary object for web content (it must be noted that conformity from a syntactic point of view, JSON-LD here, is presupposed and out of scope). I propose the angular momentum analogy as a heuristic evaluation method for assessing the compliance of agreed-upon APIs.

- The generation of compound objects has a technical cost that can only be overcome through the (IIIF) community to mitigate residual categories.

- Further processing is needed as IIIF resources with unsupported patterns are not always discarded by viewers or do not come with a warning.

- The angular momentum analogy is not to set aside the whole underlying architecture of the Web, but rather to acknowledge relevant actants within a given network.

Slide deck on Exhibit

-

Star, S. L., & Griesemer, J. R. (1989). Institutional Ecology, ‘Translations’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907-39. Social Studies of Science, 19(3), 387–420. ↩

-

Snydman, S., Sanderson, R., & Cramer, T. (2015). The International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF): A community & technology approach for web-based images. Archiving Conference, 2015, 16–21. ↩

-

Star, S. L. (2010). [This is Not a Boundary Object: Reflections on the Origin of a Concept]. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 35(5), 601–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243910377624 ↩ ↩2

-

Cross, R. (2013). The rise and fall of spinning tops. American Journal of Physics, 81(4), 280–289. https://doi.org/10.1119/1.4776195 ↩

-

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor-network-theory. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-925604-4 ↩

Leave a comment